Escape from New York

Hip-Hop 1981: A Culture in Development

With its burnt-out buildings and broken windows, the South Bronx became an emblem of urban erasure, a wound of highway-bound white flight. It was late-night monologue fodder, a cautionary movie set, and a political pawn piece. Upon visiting the neighborhood on August 5, 1980, then-Presidential candidate Ronald Reagan commented that it looked like it had been hit by an atomic bomb.[1]

When Reagan took office in 1981, conditions were no better, but something was emerging from the area. Controversial on the streets, the Sugar Hill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” had brought hip-hop to the airwaves and subsequently the suburbs; Afrika Bambaataa and the Soulsonic Force and Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five were touring the country; and those groups and Kurtis Blow had radio hits. “I didn’t see a subculture,” artist and emcee Rammellzee once said, “I saw a culture in development.”[2]

Though I didn’t know what it was called, I first heard hip-hop around this time. Copies of copies of copies, it trickled down from the Big Kids on hissy cassettes, shared via handheld recorder, Walkman, and boombox. My friends and I called it “breakdance music.” We were in middle school, a time of tribe-seeking and experimenting with identity. I’d just chosen skateboarding and BMX. Later those things would lead to DJing and keeping graffiti piece books, but breakdancing had loose ties with flatland—the spinning, gyrating strain of BMX done in empty tennis courts and parking lots. That was my thing and my entry point to hip-hop.

When I first heard it, most of hip-hop culture that existed at the time was yet to be recorded. Coming out of the electro scene in 1981, a group called Positive Messenger did a rap song called “Jam-On’s Revenge.” It was meant as a parody, but when it was re-released in 1983 as "Jam On Revenge (The Wikki-Wikki Song)," after the group changed their name to Newcleus, it was my first favorite rap song.[3] Its wacky, outsized characters and their high-pitched, cartoon voices proved the perfect initiation for my young ears, and the song contains the hallmarks of early hip-hop: catchy hooks and rhymes you could easily learn and rap along to (“Wikki-wikki-wikki-wikki… diggy dang diggy dang da dang dang da diggy diggy diggy dang dang”), lyrics about hip-hop culture itself (“‘Cause when I was a little baby boy, my mama gave me a brand new toy / Two turntables with a mic, and I learned to rock like Dolomite”), and of course, a beat you could pop and lock to. Having been re-released several times since, it’s still the song the group is most widely known for.

Though superproducer Dr. Dre cites seeing Clinton’s Parliament-Funkadelic in concert in LA as the event that opened his mind to music without limits, he also says, “My first exposure to hip-hop was ‘The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel’. That’s what started me deejaying. I think I was about 15.”[4] Released in 1981, Flash’s “Adventures...” remains the ultimate DJ cut, a cut-and-pasted collage of bits, beats, basslines, and spoken vocal samples from Chic, Queen, Blondie, Michael Viner’s Incredible Bongo Band, the Hellers, Sugarhill Gang, Sequence and Spoonie Gee, and his own Furious Five. This record and Afrika Bambaataa and the Soulsonic Force’s “Planet Rock,” which combines everything from Kraftwerk to Sergio Leone, provide the cornerstone of hip-hop composition. “To understand the magnificent creativity of the hip-hop DJ and the logical progression of today’s masters is to listen closely to both these cuts,” writes CK Smart.[5]

Long before hip-hop went digital, mixtapes—those floppy discs of the boombox and car stereo—facilitated the spread of hip-hop from the South Bronx in New York to far-flung suburbs and small towns. Hiss and pop were as much a part of the experience of those mixes as the scratching and rapping. Though we didn’t know what to call it, we stayed up late to listen. We copied and traded those tapes until they were barely listenable. As soon as I figured out how, I started making my own. A lot of people all over the world heard those early cassettes and were impacted as well. Having escaped from New York City to parts unknown, hip-hop became a global phenomenon. Every school has aspiring emcees, rapping to beats banged out on lunchroom tables. Every city has kids rhyming on the corner, trying to outdo each other with adept attacks and clever comebacks. The cipher circles the planet. In a lot of other places, hip-hop culture is American culture.

We watched hip-hop go from those scratchy mixtapes to compact discs to shiny-suit videos on MTV, from Fab 5 Freddy to Public Enemy to P. Diddy, from Run-DMC to N.W.A. to Notorious B.I.G. Others lost interest along the way. I never did, and it all started in 1981.

[To Be Continued]

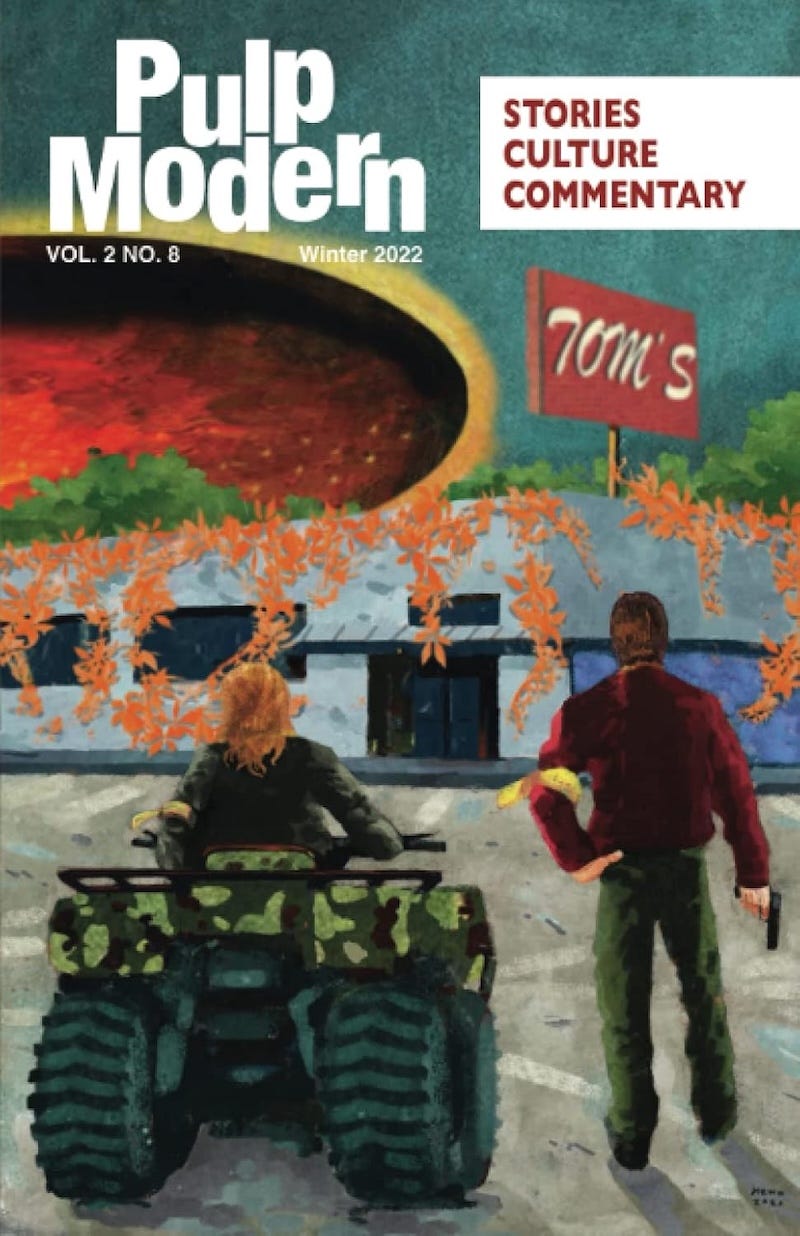

The above is an edited excerpt from my book Dead Precedents: How Hip-Hop Defines the Future (Repeater Books, 2019). In this form, it was originally published in the Winter 2022 issue of Pulp Modern. The year 1981 was the theme of the issue. Many thanks to Alec Cizak for the opportunity to correct a few factual flubs.

And thank you for reading,

-royc.

http://roychristopher.com

Notes:

[1] Parts of this piece were adapted from my book, Dead Precedents: How Hip-Hop Defines the Future, London: Repeater Books, 2019. This is a detail I got wrong in there: I said he was already president when he visited the South Bronx in 1980. Shout out to Josh Feit.

[2] Quoted in Rammellzee on the Making of “Beat Bop” (previously unpublished interview, 1999), Egotripland, March 27, 2010.

[3] In my lone TV interview so far, I mistakenly called the song “Joystick,” which was another early jam I liked in middle school. Such are the perils of memory and live television.

[4] Quoted in S. H. Fernando, Jr., The New Beats: Exploring the Music, Culture, and Attitudes of Hip-Hop. New York: Anchor Books, 1994, p. 237-238.

[5] CK Smart, A Turntable Experience: The Sonic World of Hop-Hop Turntablism, SLAP Magazine, pp. 74-75.