Ecologies need diverse species in order to survive. There is a direct correlation between the diversity of species in an ecosystem and its overall health. As its biomes homogenize, the ecosystem edges toward death, falling fallow. Viewing the mind as an ecology highlights its need for diverse inputs and ideas, lest it lose its edge to narrower and less fertile thinking.

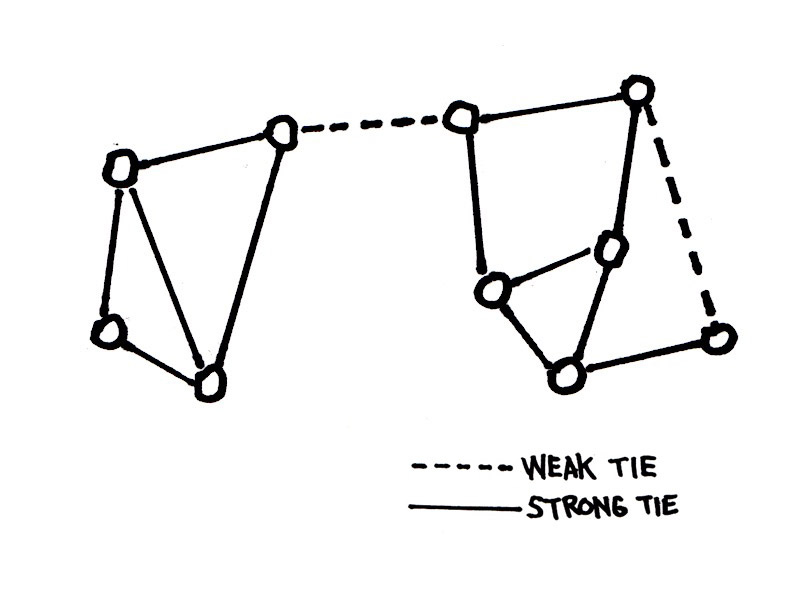

In the late 1960s, the sociologist Mark Granovetter was studying how people found jobs. His 1973 article in the American Journal of Sociology, “The Strength of Weak Ties,” states that each person in a close social network is likely to have the same information as everyone else in that network. It’s the weak ties to other networks that lead to the new stuff (see my drawing above). That is, weak ties are a more likely source of novel ideas and new information—regarding jobs, mates, and other opportunities—than strong ones. Granovetter says, “I put the theory of weak ties together from a number of things. I learned about hydrogen bonding in AP Chemistry in high school and that image always stuck with me—these weak hydrogen bonds were holding together huge molecules precisely because they were so weak. That was still in my head when I started thinking about networks.” Networks are ecologies, and their health depends on diversity.

The Hårga commune, as depicted in Ari Aster’s 2019 film Midsommar, is a case study in the power of diversity and how weak ties serve it. Following a classic slasher structure, a group of college students venture into parts unknown and are killed one by one, save the obligatory final girl. The Hårga maintain a limited genetic network, inviting new mates and their genes once a year with the election of the May Queen and the subsequent rituals, which inject the community with new seeds and fertilizer. The unwitting college kids provide that fodder in Midsommar. Ruben, the commune’s oracle, a Hårga elder explains, is “unclouded by normal cognition” because he is a “deliberate product of inbreeding.” That is, his genes have been deliberately limited, their network a closed loop.

Mark Granovetter conceived the weak ties of these cultural networks way before we were all connected online, but his insight is all the more relevant today. “Your weak ties connect you to networks that are outside of your own circle,” he explains. “They give you information and ideas that you otherwise would not have gotten.” With our personal media, ubiquitous screens, and invisible, wireless networks, we live in a world of weak ties, but you have to reach out to find the new stuff. If you let your strong ties reign, you’re headed to a dead end. If you don’t seek out diverse ideas, you risk being “unclouded” by cognition.

Further Reading:

A Message in a Bottleneck

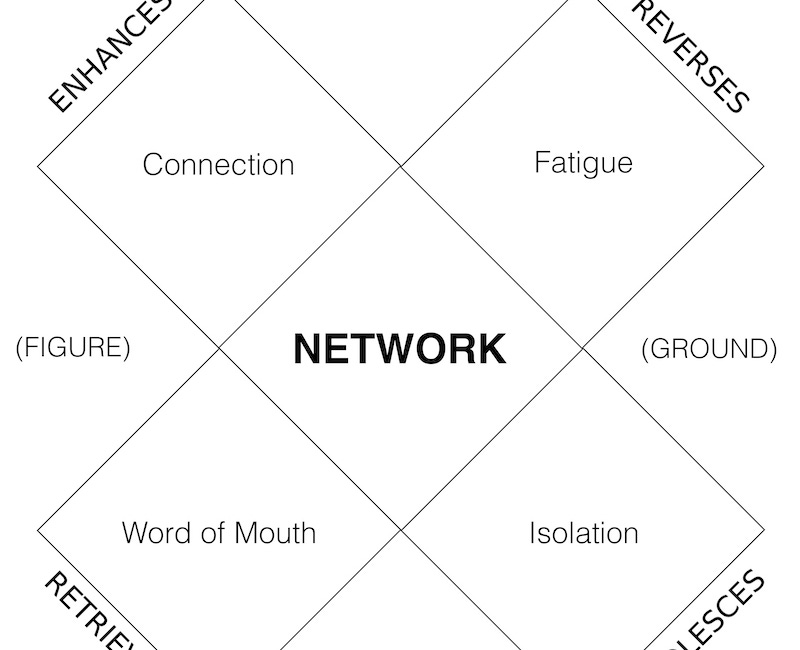

The biologist Robin Wall Kimmerer writes that when botanists go out in fields and forests looking for flora, they call it a foray, and when writers do the same, it should be called a metaphoray.[1] Marshall and Eric McLuhan open their book Laws of Media:

The Medium Picture

This bit is an edited excerpt from part of my forthcoming book The Medium Picture, about which William Gibson says, “Exactly the sort of contemporary cultural analysis to yield unnerving flashes of the future.” Douglas Rushkoff says, “Like a skateboarder repurposing the utilitarian textures of the urban terrain for sport, Roy Christopher reclaims the content and technologies of the media environment as a landscape to be navigated and explored. The Medium Picture is both a highly personal yet revelatory chronicle of a decades-long encounter with mediated popular culture.” And Paul Levinson adds, “Brilliant, pathbreaking, palpable insights… Worthy of McLuhan.”

The Medium Picture comes out on October 15th from the University of Georgia Press.

Preorder yours now! Thank you!

Thank you for reading, responding, subscribing, and sharing,

-royc.

http://roychristopher.com

Well this is a most stimulating bit of writing. It got my mind going for sure.

Thank You!

Gwyllm