New Fossils, New Futures

Celebrating Four Years of DEAD PRECEDENTS.

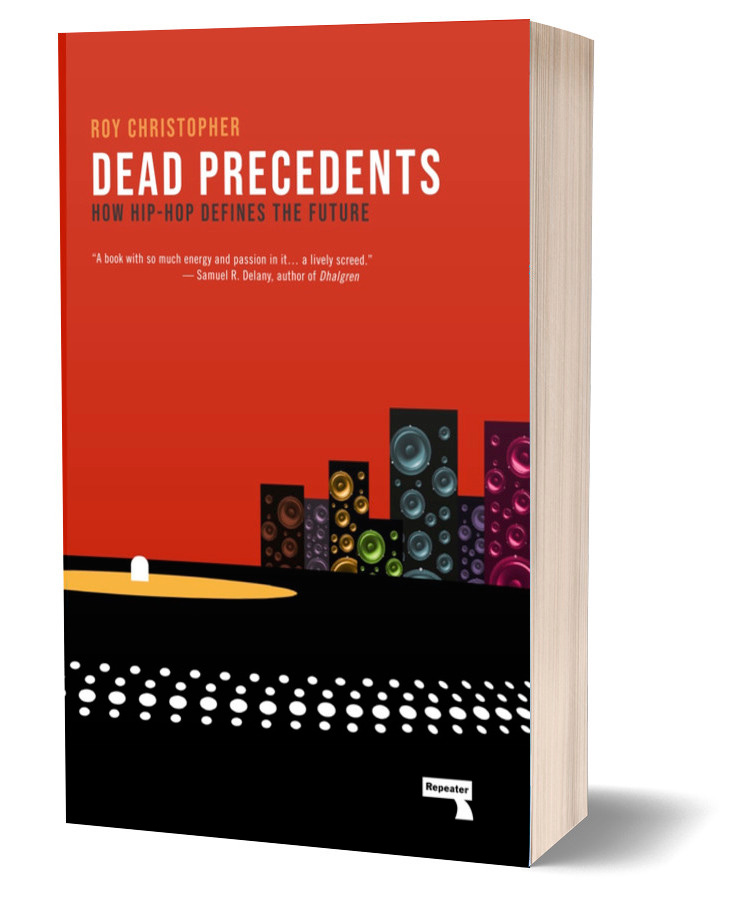

In mid-March 2019, Repeater Books published Dead Precedents: How Hip-Hop Defines the Future. Its central argument is that the cultural practices of hip-hop are the cultural practices of the 21st century. In what Walter Benjamin would call correspondences, I use evidence from cyberpunk and Afrofuturism to make the book’s many claims.

Jeff Chang, author of Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop and co-editor of Freedom Moves, says, “Roy Christopher’s dedication to the future is bracing. Dead Precedents is sharp and accelerated.” Samuel R. Delany calls it “a book with so much energy and passion in it… a lively screed.”

What follows is the brief essay that serves as the Preface to Dead Precedents.

If you don’t know, now you know.

How Hip-Hop Defines the Future

“Space, that endless series of speculations and origins — of rebirths and electric spankings — is here not so much a metaphor as it is a series of fragmented selves, a place of possibilities and debris and explorations and atmosphere.”

— Kevin Young, The Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness“Let us imagine these hip-hop principles as a blueprint for social resistance and affirmation: create sustain- ing narratives, accumulate them, layer, embellish, and transform them.”

— Tricia Rose, Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America

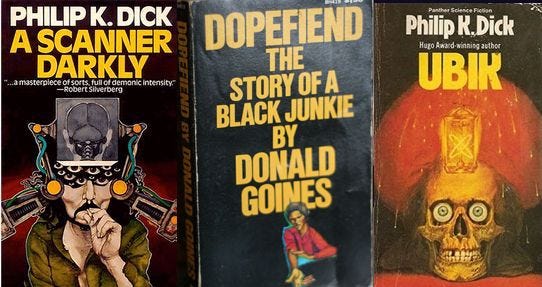

Several years ago, on one of my online profiles under “books” I listed only Donald Goines and Philip K. Dick. If you don’t know them, Donald Goines wrote about himself and his associates and their struggles as street hustlers, pimps, players, and dopefiends. Philip K. Dick wrote about the brittleness of reality, its wavy, funhouse perceptions through drugs and dreams. Goines wrote sixteen books in five years and Dick wrote forty-four in thirty. Both were heavy users of mind-altering substances (heroin and amphetamines, respectively), and both helped redefine the genres in which they wrote. They interrogated the nature of human identity, one through the inner city and the other through inner space.

While I am certainly a fan of both authors, I posted them together on my profile as kind of a gag. I thought their juxtaposition was weird enough to spark questions if you were familiar with their work, and if you weren’t, it wouldn’t matter. I had no idea that I would be writing about the overlapping layers of their legacies so many years later.

To retrofit a description, one could say that Goines’ books are gangster-rap literature. They’re referenced in rap songs by everyone from Tupac and Ice-T to Ludacris and Nas. In many instances, Dick’s work could be called proto-cyberpunk. The Philip K. Dick Award was launched the year after he died, and two of the first three were awarded to the premiere novels of cyberpunk: Software by Rudy Rucker in 1983 and Neuromancer by William Gibson in 1985.

[Ed note: If you’re interested, wrote a bit about the connections between hip-hop and literature for Literary Hub for the book’s release.]

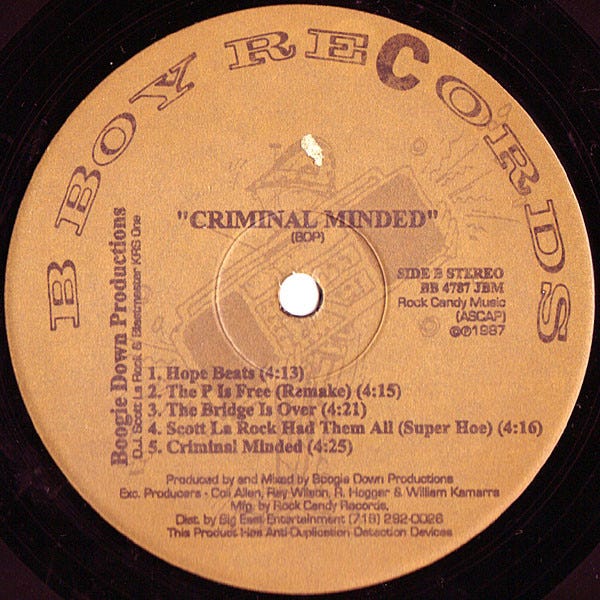

When cyberpunk and hip-hop were both entering their Golden Age, I was in high school. One day I was walking up my friend Thomas Durdin’s driveway. By the volume of the AC/DC sample that forms the backbone of Boogie Down Productions’ “Dope Beat,” I knew his mom wasn’t home. Along with the decibel level, I was also struck by how the uncanny pairing of Australian hard rock and New York street slang sounded. It was gritty. It was brash. It rocked. De La Soul’s 1996 record, Stakes is High, opens with the question, “Where were you when you first heard Criminal Minded?” That moment was a door opening to a new world.

I didn’t realize it then, but that new world was the twenty- first century, and hip-hop was its blueprint.

I distinctly remember that the label on the record spinning around on Thomas’s turntable incorrectly named the song “Hope Beats.” An interesting mistake given that DJ Scott La Rock was killed just months after the record came out, prompting KRS-One to start the Stop the Violence movement. Where Criminal Minded is often cited as a forerunner of gangster rap, KRS-One was thereafter dedicated to peace. I’d heard hip-hop before, but the unfamiliar familiarity of the “Back in Black” guitar samples in that song make that particular day stick in my head.

Long before hip-hop went digital, mixtapes—those floppy discs of the boombox and car stereo—facilitated the spread of underground music. The first time I heard hip-hop, it was on such a tape. Hiss and pop were as much a part of the experience of those mixes as the scratching and rapping. We didn’t even know what to call it, but we stayed up late to listen. We copied and traded those tapes until they were barely listenable. As soon as I figured out how, I started making my own. We watched hip-hop go from those scratchy mixtapes to compact discs to shiny-suit videos on MTV, from Fab 5 Freddy to Public Enemy to P. Diddy, from Run-DMC to N.W.A. to Notorious B.I.G. Others lost interest along the way. I never did.

A lot of people all over the world heard those early tapes and were impacted as well. Having spread from New York City to parts unknown, hip-hop became a global phenomenon. Every school has aspiring emcees, rapping to beats banged out on lunchroom tables. Every city has kids rhyming on the corner, trying to outdo each other with adept attacks and clever comebacks. The cipher circles the planet. In a lot of other places, hip-hop culture is American culture.

Though their roots go back much further, the subcultures of hip-hop and cyberpunk emerged in the mass mind during the 1980s. Sometimes they’re both self-consciously of the era, but digging through their artifacts and narratives, we will see the seeds of our times sprouting. We will view hip-hop not only as a genre of music and a vibrant subculture but also as a set of cultural practices that transcend both of those. We will explore cyberpunk not only as a subgenre of science fiction but also as the rise of computer culture, the tectonic shifting of all things to digital forms and formats, and the making and hacking thereof. If we take hip-hop as a community of practice, then its cultural practices inform the new century in new ways. “I didn’t see a subculture,” Rammellzee once said, “I saw a culture in development.”

The subtitle of this book could just as easily be “How Hip-Hop Defies the Future.” As one of hip-hop culture’s pioneers, Grandmaster Caz, is fond of saying, “Hip-hop didn’t invent anything. Hip-hop reinvented everything.” To establish this foundation, we will start with a few views of hip-hop culture (Endangered Theses), followed by a brief look at the origins of cyberpunk and hip-hop (Margin Prophets). We will then look at four specific areas of hip-hop music: recording, archiving, sampling, and intertextuality (Fruit of the Loot); the appropriating of pop culture and hacking of language (Spoken Windows); and graffiti and other visual aspects of the culture (The Process of Illumination). From there we will go ghost hunting through the willful haunting of hip-hop and cyberculture (Let Bygones Be Icons). All of this in the service of remapping hip-hop’s spread from around the way to around the world and what that means for the culture of the now and the future (Return to Cinder).

The aim of this book is to illustrate how hip-hop culture defines twenty-first-century culture. With its infinitely recombinant and revisable history, the music represents futures without pasts. The heroes of this book are the architects of those futures: emcees, DJs, poets, artists, writers. If they didn’t invent anything but reinvented everything, then that everything is where we live now. Forget what you know about time and causation. This is a new fossil record with all new futures.

Get Up On It!

Taking in the ground-breaking work of DJs and emcees, alongside writers like Philip K. Dick and William Gibson, as well as graffiti and DIY culture, Dead Precedents is a counter-cultural history of the twenty-first century, showcasing hip-hop’s role in the creation of the world in which we now live. As the book concludes, “We’re not passing the torch, we’re torching the past.”

I’m really quite proud of this book. If you don’t have it, let me know how we can fix that.

As always, thank you for reading,

-royc.

http://roychristopher.com