Accompanying their stunning, fever-dream visuals, the films of David Lynch roar with sound, what Madison Bloom at Pitchfork calls a “bowel-deep grumble.” From visceral, industrial rumbles to crackling near-silence, sound is an aspect of his movies that he valued as much as the images. “The sound design can be subliminal where you barely hear it, or sometimes you can get hit over the head with it,” said his main composer and collaborator Angelo Badalamenti in Brad Dukes’ Reflections: An Oral History of Twin Peaks (Short/Tall Press, 2014). “He creates a remarkable aural experience.”

Though I watch his movies and shows regularly, since his passing I’ve been revisiting them anew. Understandably, most of Lynch’s critics and fans focus on the visuals of his work, but there’s been a renewed interest in his attention to sound. “All the way back to Eraserhead,” said Badalamenti, who, starting as Isabella Rosselinni’s vocal coach on 1986’s Blue Velvet, composed music for almost all of Lynch’s projects. “David has loved to play and experiment with music and sound,” he said. Lynch said repeatedly that Badalamenti was the one “who really brought me into the world of music, right into the middle of it.”

Lynch explained the sound of Eraserhead in a 1977 interview:

Alan Splet and I worked together in a little garage studio with a big console and two or three tape recorders, and worked with a couple of different sound libraries for organic effects. Then we fed them through the console. It’s all natural sounds. No Moog synthesizers. Just changes like with a graphic equalizer, reverb, a Little Dipper filter set for peaking certain frequencies and dipping out things or reversing things or cutting things together. We had a machine to vary the pitch but not the speed. We could make the sounds the way we wanted them to be. It took several months to do it and six months to a year to edit it.

In the 2016 documentary David Lynch: The Art Life, Lynch told the story of how he first conceived of film and sound through painting:

I was painting a painting about four-foot square, and it was mostly black, but it had some green plant leaves coming out of the black. And I was sitting back, probably taking a smoke, looking at it, and from the painting I heard a wind, and the green started moving. And I thought, ‘oh, a moving painting, but with sound.’ And that idea stuck in my head. A moving painting.

Miguel Ferrer, who played the principled and persnickety Special Agent Albert Rosenfield in all three seasons of Lynch and Mark Frost’s Twin Peaks said, “The music was unlike any music you’d ever heard on television. […] It was so radically different and so evocative. It almost became another character.” Frequent musical collaborator Julee Cruise added, “You could scan the channels and know it was David Lynch, just three seconds in and you knew who it was. He pushes everything to the metal.”

“Oh, just let it float, like the tides of the ocean, make it collect space and time, timeless and endless.” — David Lynch describing a composition to Angelo Badalamenti

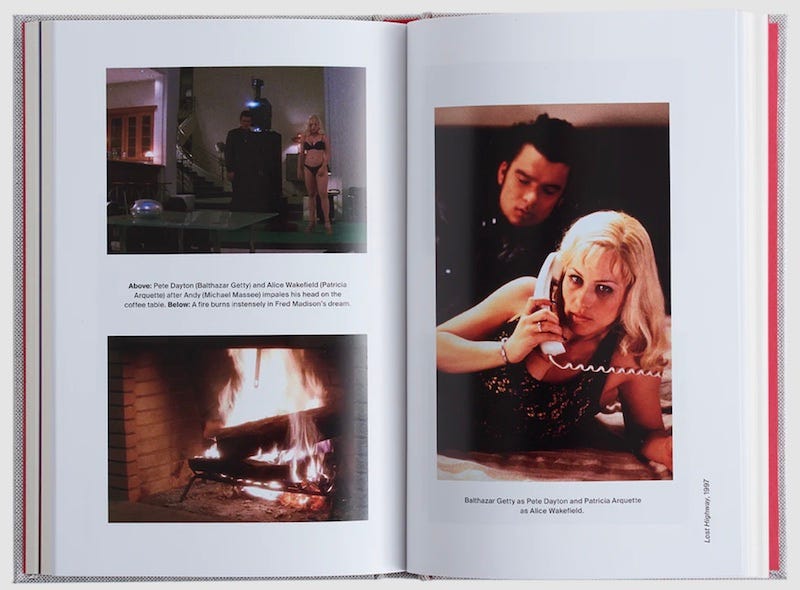

In addition to Badalamenti and Cruise, Lynch worked with Toto and Brian Eno (on the Dune soundtrack), Chris Isaak (both as a musician on Wild at Heart and an actor in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me), Trent Reznor and Marilyn Manson (on Lost Highway), Karen O (sang on Lynch’s “Pinky’s Dream”), Moby (DJed his wedding), Lykke Li (sang on Lynch’s “I’m Waiting Here”) and his own band with Badalamenti, Thought Gang (named after the Tibor Fisher book?). Almost every episode of 2017’s Twin Peaks: The Return ended with a different musical act performing at the Roadhouse: everyone from acts he’d worked with before like Rebekah Del Rio (who performed in Lynch’s Mulholland Drive and, perhaps as an homage, on the Treer Jenny von Westphalen Megazeppelin in Richard Kelly’s Southland Tales, easily his most Lynchian film), Cruise (in two episodes), and Reznor and Atticus Ross (as the Nine Inch Nails), to newcomers like the Veils, Lissie, Eddie Vedder (as Edward Louis Severson III), Au Revoir Simone, and the Chromatics (in three episodes).

Emerging from an event at the United Artists Theatre in Los Angeles on April 1, 2015, the book, Beyond the Beyond: Music From the Films of David Lynch, edited by J.C. Gabel and Jessica Hundley (Hat & Beard Press, 2016), explores the music Lynch loved and the transcendental meditation he practiced for most of his life. As the above list of artists and collaborators indicates, Lynch was one heck of a curator. Beyond the Beyond includes interviews with many of his musical collaborators, followers, and fans.

“Haunting” is an easy but apt description of Lynch’s own music but also the music he chose from other artists. He used songs by This Mortal Coil, Roy Orbison, and many others, but Chris Isaak’s “Wicked Game,” which appeared in Lynch and Barry Gifford’s Wild at Heart (1990), is perhaps the best example. Somehow both twangy and gothic, with its deep sense of longing and loss, the song was not only a big hit for Isaak but struck the core musical chord for Lynch’s on-screen images. His own “Ghost of Love” echoes a lot of Isaak’s aching darkness, billowing like a cold wind blowing through your bowels.

“I play the guitar upside down and backwards,” Lynch said in Beyond the Beyond. “I’m not a musician. It’s more about sound effects for me. I just love the sound of it.” His pure ear for sound is obviously astute. The etherial vocals of Julee Cruise illustrate the point. She put an otherworldly lilt to several of his most iconic projects.

Cruise sang on a song for Blue Velvet called “Mysteries of Love,” and her song “Falling” from her 1989 debut record Floating Into the Night, which features compositions and production by Badalamenti and Lynch, became the main theme for Twin Peaks. About that record, she told Trey Taylor at Dazed and Confused, “I’m so proud that so many young girls have picked up on it, like Lana Del Rey. And fuck anyone who says anything bad about her, because she always credits me and I think that’s the greatest honor I’ve ever received.” The clip below is from “Industrial Symphony No. 1: The Dream of the Broken Hearted,” a play directed by Lynch, with music by Badalamenti and Cruise.

So, rest in peace to David Lynch, Angelo Badalamenti, Julee Cruise, Frank Silva, Jack Nance, Frances Bay, Catherine E. Coulson, Pamela Gidley, Peggy Lipton, Lenny Von Dohlen, Miguel Ferrer, Walter Olkewicz, Kenneth Welsh, Tom Sizemore, Piper Laurie, David Bowie, Warren Frost, Michael Parks, Don S. Davis, Robert Forster, Harry Dean Stanton, and all the other passed-away alumni of Lynch Land. As Lynch himself said in a BBC interview upon the passing of Badalamenti, “I believe life is a continuum, and that no one really dies; they just drop their physical body, and we’ll all meet again, like the song says. It’s sad, but it’s not devastating if you think like that […] It’s a continuum, and we’re all going to be fine at the end of the story.”

The joyous noise they must be making…

Bibliography and Further Reading:

Richard A. Barney, David Lynch: Interviews, Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2009.

Madison Bloom, “The Eternal, Infernal Sound of David Lynch,” Pitchfork, January 17, 2025: https://pitchfork.com/features/afterword/remembering-david-lynch/

Meredith Borders, “At the End of the Story: Remembering David Lynch,” Fangoria, Spring 2025, 68-69.

Brad Dukes, Reflections: An Oral History of Twin Peaks, Nashville, TN: short/Tall Press, 2014.

J.C. Gabel and Jessica Hundley, Beyond the Beyond: Music From the Films of David Lynch, Los Angeles: Hat & Beard Press, 2016.

Olivia Neergaard-Holm, Rick Barnes, & Jon Nguyen [dir.], David Lynch: The Art Life, New York: Duck Diver Films, 2016.

Trey Taylor, “Chapter III: The Score,” Dazed and Confused, Winter 2016, 92-95.

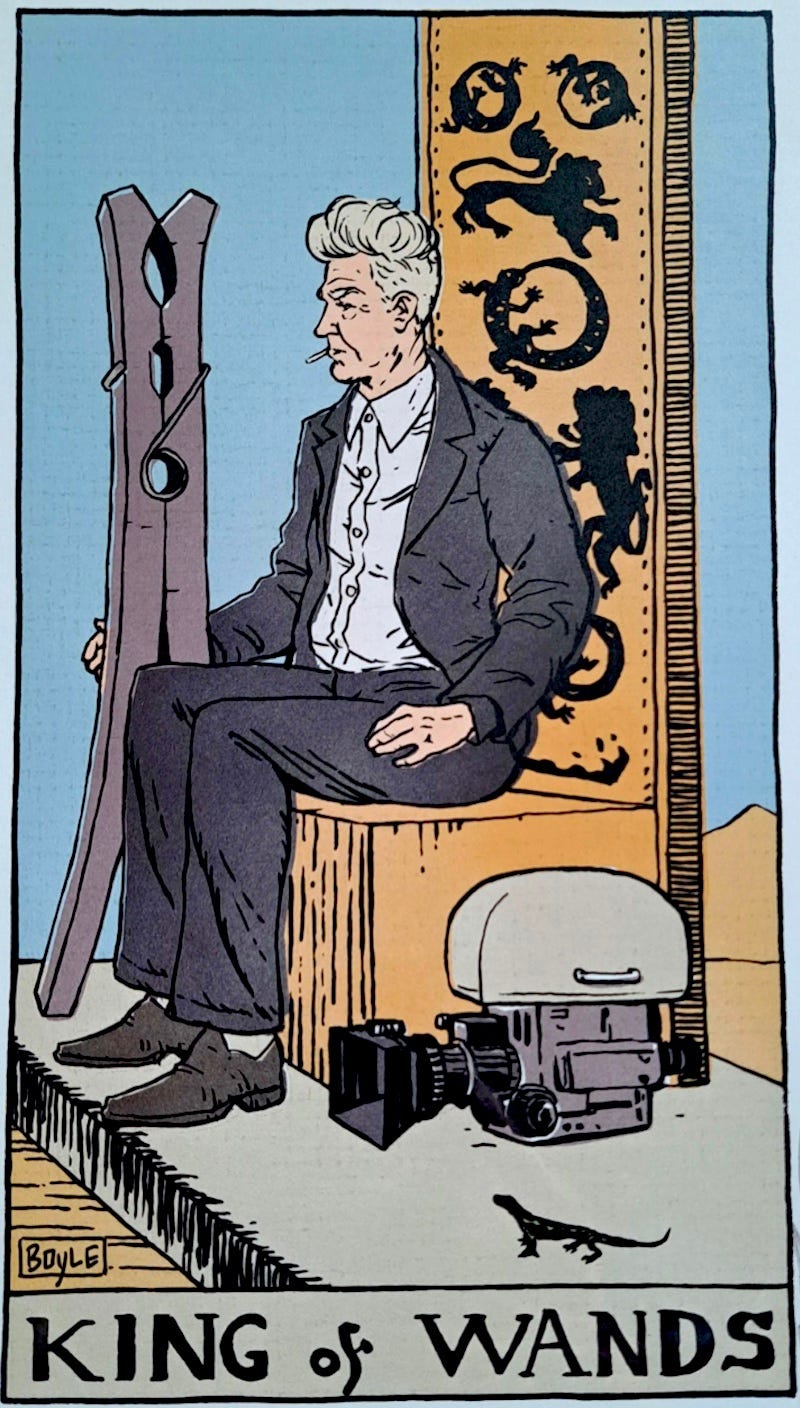

David Lynch and the Forest of Symbols

Today would’ve been David Lynch’s 79th birthday, and there’s just no way to say what his work and spirit meant to me and so many others.

Thanks for reading, responding, subscribing, and sharing,

-royc.

http://roychristopher.com

Mostly about Peter Ivers, but there is a little info about Lynch and his music here: https://ifrqfm.substack.com/p/terminal-love