The Acker Ethic

How Kathy Acker remade the world.

I’ve been thinking about allusion, quotation, and sampling in the broadest possible terms. It’s led me both deep into the self and what makes up consciousness and way, way outward into what constitutes reality. Some of the concerns are epistemological. That is, how we know what we know. And some are ontological. That is, how we be who we be. I’m zooming in and zooming out to find the limits of the concepts of reference and recycling.

Before we get to Kathy Acker’s writing practices, let’s start with brief survey of other perspectives:

In his book 2012: The Return of Quetzalcoatl (Tarcher, 2006), Daniel Pinchbeck extends Heisenberg’s idea that observation influences the observed into a Hegelian word-view that consciousness constitutes the core of reality, as if the physical world and our perception of it are merely two sides of the same phenomenon. Taken wholesale, it’s not quite solipsism, but it’s close. The act of writing blurs the lines even further.

In his introduction to Cicero’s On the Good Life, Michael Grant writes,

Cicero strongly believed that the universe is governed by a divine plan... When he looked round him at the marvels of the cosmos he could only conclude, adopting the “argument from design,” that they must be of divine origin. He was happy to adopt this form of religion, purified and illuminated by the knowledge of nature, because it justified his confidence in human beings, which was based, as has been seen, on the conviction that the mind or soul of each individual person is a reflection, indeed a part, of the divine mind.

Cicero held a distributed view of religion, each of us representing one aspect of the divine. Evoking both Immanual Kant and Jakob Johann von Uexküll in her book Ecstatic Worlds (MIT Press, 2017), Janine Marchessault writes,

Building upon Kant’s philosophy, Uexküll maintained that the world of every living organism on the earth is different from that of every other organism because of the uniqueness of its sensory organs and its environment; each creature inhabits a unique environment that is uniquely experienced. The world is thus made up of multiple, overlapping environments.

So, on one side, we’re each the eyes of the divine, but if each of us sees ourselves as the center of our own universe, then we all live in universes made up of our own observations and experiences. It’s its own many-worlds theory, even if just by a slight shift in point of view. For the sake of the discussion at hand, let’s adopt the theory—even if only by analogy. When we write, we take on a point of view, make observations, and relay experiences. Now, what if we step outside of ourselves and borrow points of view, observations, and experiences from others?

“I’m not an enclosed or self-sufficient being.” — Colette Peignot,

channeled by Kathy Acker in My Mother: Demonology

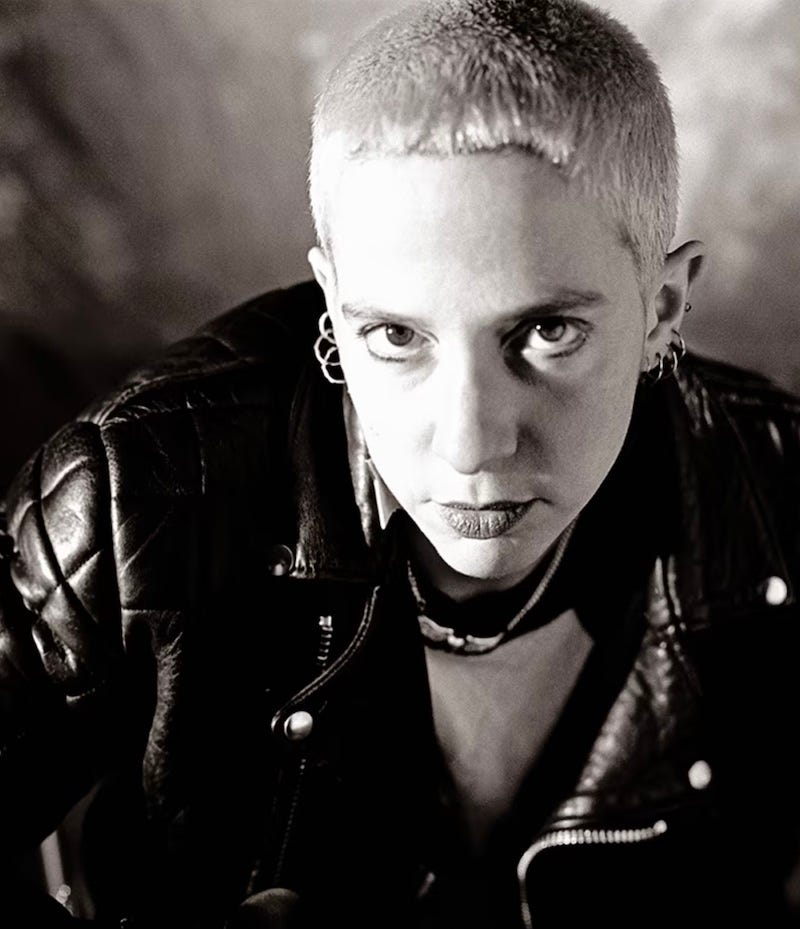

Experimental writer and all around badass Kathy Acker would do just that. Her writing practice included variations on William Burroughs and Brion Gysin’s cut-up method, parody, pastiche, postmodernism, and forms that flirted with plagiarism. During a visit to RE/Search headquarters in 2012, her friend and ex-lover McKenzie Wark told V. Vale, “She would just read a book and re-write it. Sitting cross-legged on the floor, she would just read Treasure Island and re-write it. You don’t wait for inspiration, you just get going” (italics in original). Wark met Acker in July of 1995 when she was visiting Sydney, Australia. The next year, Wark visited her in San Francisco. Their brief relationship, which largely existed between those two meetings, is chronicled via their collected emails in I’m Very Into You: Correspondence 1995–1996 (Semiotext(e), 2015).

Like everyone who came in contact with her, Wark was irrevocably inspired. Acker left no stone unthrown, no line uncrossed. Wark continues, “When I met her, she had three books… And she was writing Pussy, King of the Pirates (Grove Press, 1996). It’s one-third Treasure Island and two-thirds something else, and she would just read these three books and, almost at random, re-write them.” Acker explained her methods in a1990 interview with Sylvére Lotringer:

I placed very direct autobiographical, just diary material, right next to fake diary material. I tried to figure out who I wasn’t and I went to texts of murderesses. I just changed them into the first person, really not caring if the writing was good or bad, and put the fake first person text next to the true first person. And then continue to see what would happen. I used pre-Freudian texts because I didn’t want to deal with Freudian jargon. It was a very naive experiment at first. I was experimenting about identity in terms of language.

Like a mash-up artist or hip-hop producer, Acker would sample other texts, recontextualizing them among her own. It wasn’t a shortcut, it was an experiment, an exploration outside herself. Marchessault adds, “The environment described by Uexküll is defined by a multiplicity of overlapping subjective experiences of time.” Acker continues,

What a writer does, in 19th century terms, is that he takes a certain amount of experience and he “represents” that material. What I’m doing is simply taking text to be the same as the world, to be equal to non-text, in fact to be more real than non-text, and start representing text.

Acker was not plagiarizing or imitating but representing another’s text. It’s not mimésis or mimicry in the Aristotelian sense. A symbol on a map represents a particular building or destination, but it isn’t imitating that building or destination. As Acker added, “I didn’t copy it. I didn’t say it was mine.” She was smuggling in other points of view, other observations, other experiences, others. Hers was a proto-punk act of creative destruction.

In her Acker biography, After Kathy Acker, Chris Kraus writes, “But then again, didn’t she do what all writers must do? Create a position from which to write?” Architect of a different vector of bomb, one designed to level the pedestals of the literary canon, Acker could have proclaimed, “Now I am become life, creator of worlds.”

The Grand Allusion

I’ve been studying and writing about allusions since Matt McGlone pointed me toward them when I took his graduate class on metaphor at the University of Texas at Austin. I ended up doing my doctoral dissertation on the use of allusion in rap lyrics, and I’ve wanted to expand the idea ever since.

The above are notes for a bit in my book-in-progress, The Grand Allusion (forthcoming from Repeater Books). I am admittedly reaching past my understanding of these concepts, so I have to say thanks to McKenzie Wark and Steven Shaviro for their guidance on this topic.

And thank you for reading,

-royc.

http://roychristopher.com

Bibliography:

Kathy Acker, Hannibal Lecter, My Father, New York: Semiotext(e), 1991.

Kathy Acker & McKenzie Wark, I’m Very Into You: Correspondence 1995–1996, New York: Semiotext(e), 2015.

Kathy Acker, My Mother: Demonology, New York: Grove Press, 1994.

Kathy Acker, Pussy, King of the Pirates, New York: Grove Press, 1996.

Aristotle, Poetics, New York: Penguin Classics, 1996.

Michael Grant, Introduction, in Cicero, On the Good Life, New York: Penguin Books, 1971, 8.

Chris Kraus, After Kathy Acker: A Biography, New York: Semiotext(e), 2017.

Janine Marchessault, Ecstatic Worlds: Media, Utopias, Ecologies, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2017.

Steven Shaviro, Doom Patrols: A Theoretical Fiction About Postmodernism, San Francisco, CA: Serpent’s Tail, 1996.

V. Vale, A Visit from McKenzie Wark, San Francisco, CA: RE/Search Publications, 2014, 21.

McKenzie Wark, Philosophy for Spiders: On the Low Theory of Kathy Acker, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021.

Blood and Guts in High School is a stone cold classic