On his spoken-word album Bomb the Womb (Gang of Seven) from 30 years ago, Hugh Brown Shü does a great bit about it being 1992, and everything seeming familiar. “What has been will be again,” reads Ecclesiastes 1:9. “What has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.” That old familiar feeling has been around longer than we’d like to admit, but how do make sense of things that seem familiar but really aren’t?

The first time I heard “The Pursuit of Happiness” by Kid Cudi (2009), I felt like something was a bit off about it. I felt like it had originally be sung by a woman, and he’d just jacked the chorus for the hook. I distinctly remembered the vocals being sung by a woman but also that they were mechanically looped, sampled, or manipulated in some way.

Upon further investigation I found that the song was indeed originally Kid Cudi’s, but that Lissie had done a cover version of it. Her version is featured in the Girl/Chocolate skateboard video Pretty Sweet (2012), which I have watched many times. Even further digging found the true cause of my confusion: A sample of the Lissie version forms the hook of ScHoolboy Q’s song with A$AP Rocky, “Hands on the Wheel.” This last was the version I had in my head and the source of my confusion.

I use this rather tame example to show how easy it is to be unsure about the source of something that we feel like we know. Our memories play tricks, but so do our media. The phenomenon plays out in many other contexts as well.

The cover art for Playboi Carti’s newest record, Whole Lotta Red (2020) knocks off the lo-fi aesthetic of classic punk magazine Slash. This isn’t the first time Carti’s visual aesthetic has paid homage to punk.

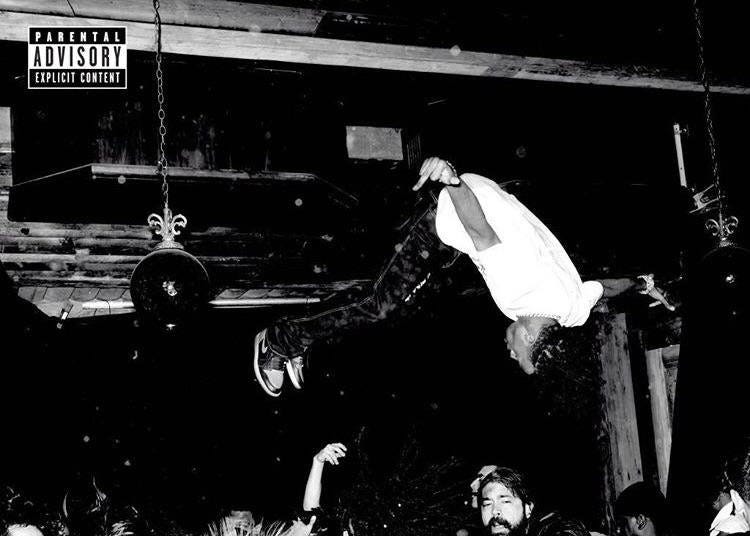

The stage-diving photo on the cover of his last record, Die Lit (AWGE/Interscope, 2018), recalls a similar SST promo photo of HR of Bad Brains, who was notorious for doing backflips on stage. It’s closer to Edward Colver’s classic 1981 Wasted Youth live shot, which appeared on the back of their Reagan’s In LP (ICI Productions, 1981).

Such allusions are everywhere in our media. They’re also prevalent in human interpersonal communication. The example I always cite for this comes from Adbusters Magazine founder Kalle Lasn. In his 1999 book Culture Jam, Lasn describes a scene in which two people are embarking on a road trip and speak to each other along the way using only quotations from movies. Based on this idea and the rampant branding and advertising covering any surface upon which an eye may light, Lasn argues that our culture has inducted us into a cult: “By consensus, cult members speak a kind of corporate Esperanto: words and ideas sucked up from TV and advertising.” Indeed, we quote television shows, allude to fictional characters and situations, and repeat song lyrics and slogans in everyday conversations. Lasn argues, “We have been recruited into roles and behavior patterns we did not consciously choose” (emphasis in original).

Lasn writes about this scenario as if it is a nightmare, but to many of us, this sounds not only familiar but also fun. Our media is so saturated with allusions to other media that we scarcely think about them. A viewing of any single episode of popular television shows Family Guy, South Park, or Robot Chicken yields allusions to any number of artifacts and cultural detritus past. Their meaning relies in large part on the catching and interpreting of cultural allusions, on their audiences sharing the same mediated memories, the same mediated experiences.

In an article from 2015, Devin Blake uses comedy as an example. Pointing to the well-established fact that we no longer define ourselves by what we produce but by what we consume, he marks the rise of what he calls “consumer comedy.” That is, comedy that references other media in order to pack its punchlines. “A lot of what happens in late night TV, for example,” he writes, “seems to involve things that we consume, namely other media like TV shows, movies, and music.” The added knowledge of an allusion is crucial for comedy in that if the audience doesn’t catch a reference, they won’t get the joke. Blake adds the critical insight: “A world of comedy-for-consumers is different than one filled with comedy-for-producers.” The consumption of information is not tethered to the physical world in the way that the production of material goods is.

Marshall McLuhan would frame these media allusions in Gestalt psychology terms as figure and ground. The figure being the overt reference—visual, verbal, or otherwise—and the ground being the invisible referent—the original image or text. “The figure is what appears and the ground is always subliminal,” he wrote. In the visual allusions above for instance, the figure is what you see, and the ground is the source material, the knowledge you have that you’ve seen the thing before, that old familiar feeling. The figure is the artifact at hand, and the ground is the historical context it’s indexing.

So widespread is the use of allusion in our media that it has become its own cultural form. Following allusions on a path through media provides a unique way to understand contemporary mediated culture. Because allusion relies on shared media memories, exploring its use and function in media and conversation helps answer questions of how such mediated messages are stored, conceived, retrieved, and received.

Allusive tactics are not limited to television shows, movies, music, and conversations. Users employ them on social media as a form of “social steganography.” That is, hiding encoded messages where no one is likely to be looking for them: right out in the open. In one study, a teen user has problems with her mother commenting on her status updates. She finds it an invasion of her privacy, and her mom's eagerness to intervene squelches the online conversations she has with her friends. When she broke up with her boyfriend, she wanted to express her feelings to her friends but without alarming her mother. Instead of posting her feelings directly, she posted lyrics from “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life.” Not knowing the allusion, her mom thought she was having a good day. Knowing that the song is from the 1979 Monty Python movie, Life of Brian, and that it is sung while the characters are being crucified, her friends knew that all was not well and texted her to find out what was going on.

Social steganography is not always so innocuous. Media allusions are arguably more vital on social media where memes are the currency exchanged. Conspiracy theories are spread online through shared texts as their adherents rally around allusions to those texts. The hidden knowledge allows these groups to communicate with each other out in the open without alarming others or stirring up ire or opposition. So-called “dog whistles,” these allusions are shibboleths shared by members and ignored by others. QAnon has largely shared references to their own rumors and accusations, but other texts like William Luther Pierce's The Turner Diaries and the Luther Blissett Project’s novel Q are also touchstones. On the possible connections between the Q of QAnon and the Q novel, Luther Blissett member Wu Ming 1 says, “Once a novel, or a song, or any work of art is in the world out there, you can’t prevent people from citing it, quoting it, or making references to it.”

If we’re all watching broadcast television, we’re all seeing the same shows. If we’re all on the same social network, no two of us are seeing the same thing. The limited access to content via broadcast media used to unite us. Now we're only loosely united via the platform, and the platform itself doesn't matter. What matters is ephemeral and esoteric knowledge, knowing the memes, getting the references, catching the allusions. The references are stronger than their original media vessels. As less and less of us share the ground of each figure, the latter outmodes the former as it shrinks. Whether images from other media or quotations from a text, the allusions themselves outmode the vehicles that carry them.

Bibliography:

Blake, Devin, “The Rise of Consumer Comedy,” Splitsider, 2015 [archived here].

Blissett, Luther, Q: A Novel. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2003.

boyd, danah & Marwick, Alice E. Social Privacy in Networked Publics: Teens’ Attitudes, Practices, and Strategies. Paper presented at Oxford Internet Institute’s A Decade in Internet Time: Symposium on the Dynamics of the Internet and Society, Oxford, England, September 22, 2011.

Brown Shü, Hugh, Bomb the Womb, New York: Gang of Seven, 1992.

Brunton, Finn & Nissenbaum, Helen, Obfuscation: A User's Guide for Privacy and Protest. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015.

Frankel, Eddie, QAnon: The Italian Artists Who May Have Inspired America’s Most Dangerous Conspiracy Theory, The Art Newspaper, January 19, 2021.

Greaney, Patrick. Quotational Practices: Repeating the Future in Contemporary Art, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

Lasn, Kalle, Culture Jam: The Uncooling of America, New York: Eagle Brook, 1999, p. 53.

McLuhan, Marshall, Understanding Media, New York: Houghton-Mifflin.

Molinaro, Matie, McLuhan, Corinne, & Toye, William (Eds.), Letters of Marshall McLuhan, New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Pierce, William Luther (as Andrew Macdonald), The Turner Diaries, Charlottesville, VA: National Vanguard Books, 1978.

As you may have noticed, there are a lot of tenuously connected ideas bouncing around in this one. It’s kind of a rough draft. I’ve been trying to apply my study of media allusions to the weird ways information moves around online. Thank you for enduring my thinking aloud.

In other news, our edited collection, Boogie Down Predictions: Hip-Hop, Time and Afrofuturism, which is forthcoming from Strange Attractor Press, is up on Amazon for preorder already! I’ll tell you more about it as the release date approaches. It’s so dope. Get yours now!

As always, thank you for reading, responding, and sharing!

Power to you,

-royc.